VULNERABILITY

THREATENED, ATTACKED, SUED, AND SMEARED

Independent and investigative journalism has its price.

Almost half of the publishers in this survey said members of their staff had suffered blackmail, threats, or violence because of their journalistic work.

Digital natives pay a price for pursuing the truth

Kidnapping, physical threats, lawsuits, hacking, and audits are among the challenges reported by the digital natives in this study.

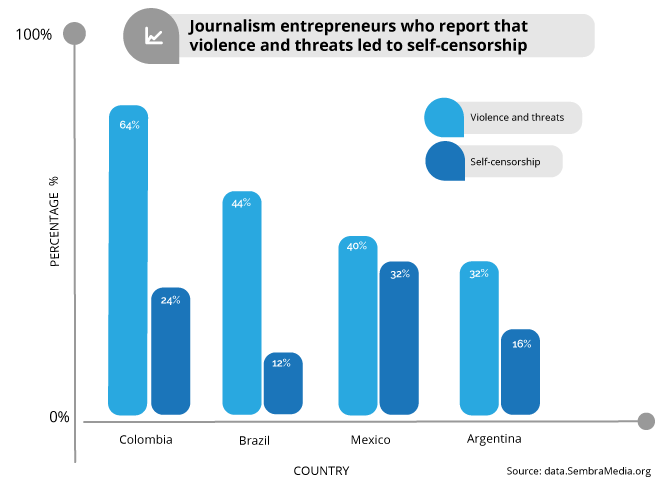

More than 45% have been subject to threats or violence because of their reporting, and many respondents said intimidation and physical threats had led to self-censorship.

More than 20% of the organizations admitted that they avoided covering certain topics, people, and institutions because of threats and intimidation.

Lawsuits are also used to try to censor journalists. After Congresso em foco in Brazil published a story about the “super salaries” of government officials exceeding the legal limit, they were hit with an orchestrated attack of 50 lawsuits.

To date, they’ve won 48. The last two are pending, but the cost of attending hearings around the country had a big impact on their finances.

In Mexico and Argentina, a favorite government tactic has been to initiate a seemingly unending tax audit of a publication.

Digital attacks are an increasingly common form of censorship and retaliation.

Half of the organizations had suffered cyberattacks because of their news coverage, ranging from hacked email and social media accounts, to distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, to digital smear campaigns.

In a DDoS attack, a hacker uses thousands of compromised computers to overload a website, making it impossible for anyone else to visit.

Anyone can pay to launch a DDoS attack against a competitor, political rival, or a journalist’s website for as little as $5, using services readily available on the dark web.

This digital form of censorship is on the rise in Latin America (and around the world) and has become such a common problem that Google developed Project Shield, a free service designed to protect the websites of journalists, human rights organizations, and election monitors.

The nonprofit eQualit.ie in Canada offers DDoS protection with its Deflect service, as well as hosting and technical support.

Yet many digital natives are still not protected because they are not aware of these services or lack the time and skills to get them set up.

Hacking journalists’ email accounts also appears to be on the rise. A New York Times article published June, 2017, notes, “Carmen Aristegui, one of Mexico’s most famous journalists, was targeted by a spyware operator posing as the United States Embassy in Mexico, instructing her to click on a link to resolve an issue with her visa.”

Although the article noted that there was no ironclad proof the government was responsible, “The Mexican government’s deployment of spyware has come under suspicion before, including hacking attempts on political opponents and activists fighting corporate interests in Mexico.”

“We have suffered many cyberattacks. Once they replaced all the images on our site with pornography. We lost a lot of content and it took us a week to replace all of our images.

We were hit several times by a system that uses its server to redirect traffic from online stores.

This makes our website very slow and makes it impossible to update. After it happened a few dozen times, we had to migrate to a more robust infrastructure.”

— Dal Marcondes,

Editor of Envolverde, Brazil

Seeking editorial independence, and suffering for it

In their mission statements, nearly all the sites we studied in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico emphasized their desire to differentiate their work by being editorially independent.

They expressed dissatisfaction with traditional media in their countries for colluding with vested interests, failing to report on sensitive topics, and ignoring provincial and rural areas.

Their manifestos declared that their communication was more horizontal, conversational, explanatory, accessible, and more user friendly than traditional top-down journalism.

Driven by a mission of public service, journalist-led news organizations routinely put readers, and even personal safety, ahead of profitability.

More than 25% of the organizations said that their coverage of government and business had caused them to lose advertising or otherwise suffer economic hardship.

This supports our anecdotal findings in the region that many journalists are inspired to develop new media ventures because they are frustrated by the polarization in their countries.

Animated film shows the terror of a journalist’s kidnapping

Pie de Página of Mexico produced a short, animated film to dramatize the story of the kidnapping and torture of photojournalist Luis Cardona.

The film, “I am No. 16” was narrated by Cardona himself and illustrated by the artist Rapé, whose animations put the viewer inside the experience of terror, pain, and uncertainty in a way that mere words never could.

The title refers to the fact that Cardona had spent months profiling the disappearances of 15 young men who were low-level workers in the drug trade in his hometown of Nuevo Casas Grande, near the embattled city of Ciudad Juárez.

The armed men in military uniforms who abducted him repeatedly told him to stop reporting these stories or he would be killed.

The film was made possible through a collaboration with the European Union, Instituto Mexicano de Derechos Humanos y Democracia, and Periodistas de a Pie.

Both the journalist and the artist who worked on the video have had to move away from their hometowns because of death threats. Watch the video on YouTube.

Illustrations from the animation used with permission from the artist Rafael Pineda, Rapé.